Parents, students consider impact of Code Red drills

WEB EXCLUSIVE

The shooting at Majory Stoneman Douglass High school was only a 3 hour drive from Oviedo—too close to home for many OHS families.

“With each mass shooting that happens, the reality comes just a little bit closer,” said mother of three Nadine Nasby. “I don’t doubt there’s a parent or student who, when they say goodbye in the morning before school, that all of them have that thought of, ‘Could this be the last time we see each other?’”

Sophomore Rachel Nasby stated that she, like her mother, does think about mass shootings on campus.

“It does terrify me at the thought that one of my classmates knocking on the door could instead be a gunman,” R. Nasby said. “However, I do try to not live in fear.”

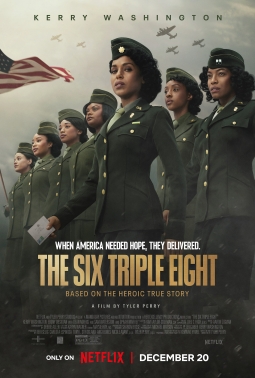

Ever since the Sandy Hook shootings, Code Red drills have become commonplace activities in schools. These drills allow students and faculty the opportunity to practice emergency procedures in case of an active shooter.

Father of three Scott Gillis said that Code Red drills create stressful situations.

“From the perspective of a parent, it always horrifies you,” Gillis said. “We recently got a text from our 16-year-old regarding such a drill. The effect stayed with her mother for days.”

For students, the drills can be a cause of anxiety. Students must turn off all the lights, lock the doors and sit in silence until an “all clear” is given.

“At first, it is kind of scary, and everyone is scared because you don’t know if it’s real or not,” said senior Andrew Aguirre. “It’s a concern because with all the shootings that have been happening, you don’t know if it’s going to be real.”

The drills are not any fun, according to junior Laura Hidalgo.

“It’s always uncomfortable, hiding from the door cramped next to students in your class,” Hidalgo said. “I also always get anxious that it may be a real code red and not just a drill.”

The fact that so much in Code Red drills are unknown is what makes Aguirre nervous.

“If something does come up, I’m never going to know because we have so many drills,” Aguirre said. “I don’t think there should be that many drills because if something does occur and if people think that it’s not real, then our safety is definitely at risk. It’ll be like the boy who cried wolf and if it happens no one will be prepared.”

Changing Times

Since most parents have never been through a Code Red drill, their fear is of the unknown.

“When I was a kid, we just had simple fire drills and I thought that was scary enough,” N. Nasby said.

Mother of four sons Rebecca Gruse stated that no other drills were practiced during her schooling. For Gillis, nuclear missile drills were the closest he ever came to a Code Red drill.

“I went to elementary school toward the official end of the Cold War era and the threat of that time was nukes,” Gillis said. “At a given moment, we would be told to cram ourselves under our little desks and interlock our fingers over our heads.”

According to Gillis, he imagines that drills can become less scary for students over time.

“From the perspective of a developing child, I would imagine it ranging from a horrifying experience to eventually becoming a mundane drill,” Gillis said.

Junior Bailey Hopkins agrees that drills have become normal to her.

“They feel like a joke,” Hopkins said. “Honestly, I assume they are drills because I have no reason to feel otherwise.”

Junior Starla Pempey-Smiley name agrees the drills have become predictable to her.

“When there is an unannounced Code Red drill, I think ‘This is a drill,’” Pempey-Smiley said. “I’ve had a lot of Code Red drills in my high school history, so it’s just like it’s probably not true.”

Perception of Seriousness

Some students feel as though their classmates don’t take the situation seriously enough.

“Students should act like their life is in danger,” Pempey-Smiley said. “They do drills for a reason, so you know how to be if there is ever a situation, but no one takes it seriously, and they should.”

Aguirre said that there is always someone who does something not serious.

“People are joking around and even though every time it has been a drill,” Aguirre said. “We never know when it could be real and joking around risks our safety.”

According to dean Jason Maitland, the school district, in corroboration with the Sheriff’s office, wants schools do two Code Red drills per year.

“One of those drills is announced and the other one is unannounced,” Maitland said.

Maitland said that unannounced drills intend to make the practice as real as possible, but not to make anyone scared.

“But, if everyone knows it’s coming, it kind of defeats the purpose of a drill,” Maitland said.

Hidalgo finds that whether or not a Code Red is announced does change the seriousness of the situation.

“If it is announced, many people do not take the Code Reds seriously,” Hidalgo said. “But, if it is an unannounced drill, people tend to behave better and stay quiet. I tend to do the same, which is a bad habit as we should take them seriously.”

Hidalgo stated that the shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School may impact the Code Red schedule.

“I believe we will probably see an increase in our Code Red drills because school shootings are so evident in the United States at the moment and our faculty probably want us to be as prepared as possible if anything like that were to happen at our school,” Hidalgo said.

However, for other students Code Reds are just another drill in which schools have to complete.

“They feel like a waste of time,” said junior Ana Vanravensway. “They’re showing us how to protect ourselves in that situation, but I feel like none of the stuff we do would actually protect us.”

Gillis stated that he fears the frequency of drills will train students to behave a certain ways.

“I’m afraid that the drills are either being run so frequently that the students will become desensitized to the idea of the event or not often enough where if the event were to actually take place, panic would be the prevailing factor and that will ultimately lead to the injury or death of more students than necessary,” Gillis said.

Some people think that Code Red drills are going to become the norm, like fire drills.

“As far as frequency goes, I think twice a year is sufficient,” Maitland said. “I do think it’s something that’s a good thing that should continue to happen.”

Safety Analysis

Hopkins worries that the drill isn’t helping students be safer.

“In the Code Red drill we have now, we are all just kind of sitting ducks in that situation, locking ourselves in a room,” Hopkins said. “It’s like a horror movie when they lock themselves in closets.”

Vanravensway stated that for the amount of students on campus, the current drill is the safest option.

“I think sitting in a room is the best option you can have because there are so many students in this school,” Vanravensway said. “It would be mayhem if you tried to do differently. I feel like they position us well in the classroom, but there’s no way to really make it safer.”

Nikolas Cruz, the alleged shooter at Majory Stoneman Douglass High School, pulled the fire alarm to draw students out of their classroom so that he could shoot them, which introduces fears for when students are outside of classrooms.

According to N. Nasby, the campus as a whole could be improved for safety.

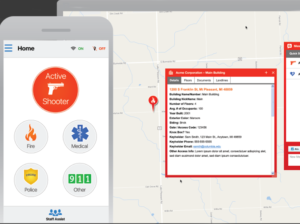

“I have often thought as I would sit in the parking lot by building 8 waiting to pick my daughter up, how easy it would be for someone to come on campus at the end of the day at dismissal,” N. Nasby said. “I would like to see cameras that can be viewed from the office or other central station where someone can possibly see an intruder coming or possibly pulling a fire alarm.”

Recently, OHS has added numerous cameras around campus, which Maitland has access to, in hopes of making the campus safer.

Gillis stated that buildings could be improved for the event of a shooter.

“Schools should consider modifying existing school buildings for the addition of adequate cover from gunfire, whether that is in each classroom or a centralized area accessible from nearly anywhere on the school campus,” Gillis said. “Also, the inclusion of devices that help lock down doors to classrooms in the event of a shooting. A shooter cannot shoot what they cannot access.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Oviedo High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting and printing costs. Thank you!

![Prom king Colin Napier and queen Leah Hopkins dance the night away during the Golden Gala on April 26th. Prior to the prom, the Student Government must make many preparations over the course of months in order to ensure it goes off without a hitch. However, their work eventually pays off when it comes time for the dance. “We set up [the prom] the day before, and it’s horrible. We’re there for a very long time, and then we get our beauty sleep, and then we get ready for prom the next day,” Aubrie Sandifer said.](https://oviedojournalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Oviedo-197-800x1200.jpg)

![Hopkins at Honor Grad with golf coach John McKernan. As Hopkins’ golf coach for the last two years he has seen Hopkins’ growth as a player and person along with their contributions to the team. “[Hopkins] has just been really helpful since I took [the golf team] over, just anything I wanted to do I ran by [Hopkins],” said McKernan.](https://oviedojournalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/B66A7760-800x1200.jpg)

![Prom king Colin Napier and queen Leah Hopkins dance the night away during the Golden Gala on April 26th. Prior to the prom, the Student Government must make many preparations over the course of months in order to ensure it goes off without a hitch. However, their work eventually pays off when it comes time for the dance. “We set up [the prom] the day before, and it’s horrible. We’re there for a very long time, and then we get our beauty sleep, and then we get ready for prom the next day,” Aubrie Sandifer said.](https://oviedojournalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Oviedo-197-400x600.jpg)

![Hopkins at Honor Grad with golf coach John McKernan. As Hopkins’ golf coach for the last two years he has seen Hopkins’ growth as a player and person along with their contributions to the team. “[Hopkins] has just been really helpful since I took [the golf team] over, just anything I wanted to do I ran by [Hopkins],” said McKernan.](https://oviedojournalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/B66A7760-400x600.jpg)

Anonymus • Nov 25, 2020 at 2:18 AM

I feel as if code red drills do not actually work. If the person is from the school, they know all of the protocol for code reds and they know how to access buildings, all these safety precautions would have gone to waste.

Kaitlyn M Montcrieff • Feb 23, 2018 at 9:26 PM

Great article! I loved reading the different perspectives from students.