Holden Caulfield, young adult fiction, and the larger trend of anti-intellectualism

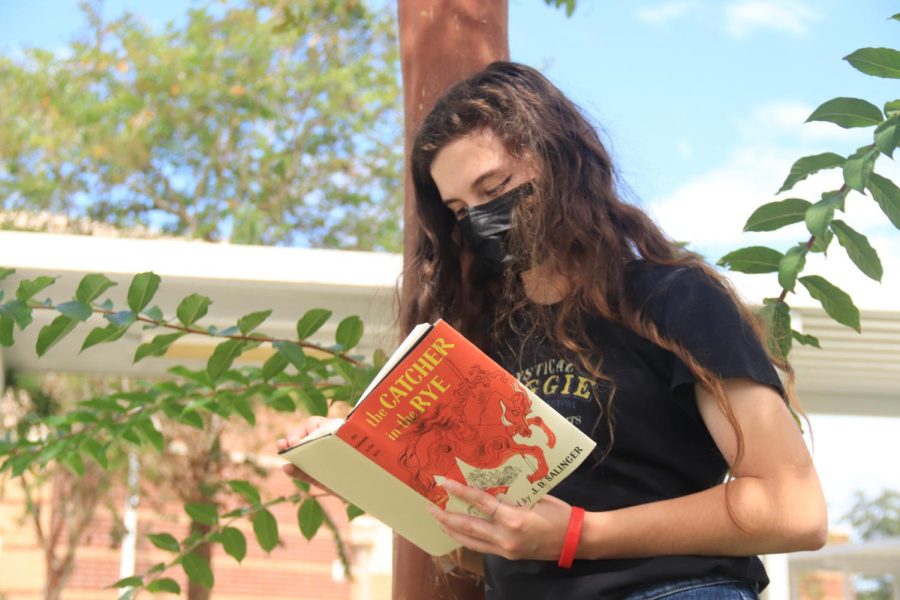

Junior Ella Ferrell enjoys The Catcher in the Rye under a tree.

September 23, 2022

If one had not previously read (or, if they “read”) J.D. Salinger’s 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye, and their only exposure to it was opinions within popular discourse, they may begin to develop some erroneous assumptions. Truly, they may think that the novel is a filthy, American Psycho-esque collection of word vomit about a mass-murdering, puppy-killing, and unapologetically sexist slacker with absolutely nothing to offer to the world. The objective plot of the novel, which is about a traumatized and disillusioned victim of sexual abuse’s manic episode, is often not discussed. For many, it is less taxing intellectually to moan about how annoying they found a character than to examine why they may act the way that they do.

The true irony of this predicament is that many of these individuals acted (or, act) exactly like clones of Holden Caulfield. The protagonist of Catcher is not irritating for any other reason other than the fact that he is a sixteen-year-old boy; he does not possess any inherent, ontological evil that is unlike the average adolescent’s angst. Of course, his monologues and rants are a bit uncomfortable and morally questionable at times, but this is a feature, not a bug. Catcher, at its core, is a novel about innocence and disillusionment in the face of adulthood from the perspective of a traumatized young man.

From an intellectually lazy perspective, honest literary criticism is always about how moral the protagonist is. Well-written books, from this perspective, are feel-good and easily digestible stories about triumphant characters and ideals. Poorly-written books, however, are about people much more like ourselves than any archetype. These protagonists are complicated, grey, and may do or say things that seem illogical to the reader. Of course, these complex characters may take a bit of analysis and brain-power that is above your average children’s fantasy novel. Thus, one is only met with superficial criticism about how someone didn’t like the narrator’s word choice or how the protagonist should have gotten therapy.

Young-adult, or, YA literature, has its place. The argument is not a pretentious and elitist dismissal of the genre as a whole. However, not all literature needs to have the characteristics of YA, and the rhetoric that it does has had exceedingly depressing consequences. On popular social media platforms, books are advertised through an endless stream of digestible, marketable, mass-appealing, fanfiction-esque tropes, and critical analysis is no longer fashionable. Oftentimes, a classic novel is dismissed on the sole grounds that it is a classic, and that they might have been forced to read it by their rude ninth-grade English teacher that might have made them write a five-sentence ‘essay’ a few times. The fact that literature and analysis of it is more than what they were taught in school is lost on most.

The argument is also not an uncritical endorsement of books that feature immoral things. Of course, if a book’s themes are supportive of some sort of evil, then that is a fundamental issue with the work itself, and the book should not be endorsed. However, the portrayal of something (with a thematic condemnation of it) is not akin to an endorsement. Crime and Punishment, American Psycho, and The Tell-Tale Heart are not political pamphlets for the legalization of murder. The themes of these stories are obvious condemnations of the behaviors of their protagonists. The Catcher in the Rye does not endorse underage drinking, rudeness, or delinquency; thematically, it shows that these are consequences for how one is treated.

From the perspective of the intellectual slacker, the above novels fall short of the literary ideal solely because of their portrayal of unsavory actions or questionable protagonists. Truly, Raskolnikov, Patrick Bateman, and Poe’s neurotic protagonist should have just all gone to therapy. After all, isn’t the goal of every literary work to achieve a morally good and triumphant ending?

Obviously, to the rational person, such a position is nonsense. The goal of literature is to explore the human condition and the themes of our society. It cannot do this with the expectation of the complete morality of all protagonists. Sometimes, protagonists need to be more like us than the average YA fantasy protagonist. Sometimes, protagonists need to be downright evil.

![Prom king Colin Napier and queen Leah Hopkins dance the night away during the Golden Gala on April 26th. Prior to the prom, the Student Government must make many preparations over the course of months in order to ensure it goes off without a hitch. However, their work eventually pays off when it comes time for the dance. “We set up [the prom] the day before, and it’s horrible. We’re there for a very long time, and then we get our beauty sleep, and then we get ready for prom the next day,” Aubrie Sandifer said.](https://oviedojournalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Oviedo-197-800x1200.jpg)

![Hopkins at Honor Grad with golf coach John McKernan. As Hopkins’ golf coach for the last two years he has seen Hopkins’ growth as a player and person along with their contributions to the team. “[Hopkins] has just been really helpful since I took [the golf team] over, just anything I wanted to do I ran by [Hopkins],” said McKernan.](https://oviedojournalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/B66A7760-800x1200.jpg)